Revelations: Bitter History, Enduring Spirit in the Art of Daniel Minter

By Henry John Drewal

Daniel Minter’s exhibition/installation entitled OTHERED: Displaced from Malaga is a meditation on the concept and meaning of home in histories of genocide, enslavement, racism, oppression, segregation, disenfranchisement, and incarceration – all manners of denigration and displacement – part of this country’s past and present that we forget, diminish, or deny. How and when do we feel “at home” with ourselves and with others and what are the forces that cause us to feel adrift, rootless, disrupted and displaced from “home”? These are central questions at the heart of Daniel Minter’s art and the saga of the Malaga Island community, an interracial community marked by difference, by its blackness and hybridity. Its otherness, feared and judged a threat by the dominant, white community, had to be “disappeared.” Yet Daniel’s art has made it immortal.

The story of the Malaga Island community is but one local episode revealing the depth and pervasiveness of abiding racism in this country, whether south or north, east or west, past or present. The racism that destroyed the lives of those families on Malaga Island occurred during the rise of the pseudo-science of eugenics, the false belief that genes (and head size and shape measured with calipers) determined a person’s intelligence or attributes, and that immoral or criminal behavior was hereditary. Such thinking shaped the post-Civil war period misnamed “Reconstruction” which in reality was one of grave danger and destruction for African-Americans and others (Native Americans, Asians, Jews) with the rise of white terrorists of the KKK, widespread lynching, unfulfilled promises of land and support (“40 acres and mule”), America’s Apartheid named “Jim Crow,” and its present iteration as mass incarceration. Nationally, all these developments and social forces, plus local political and economic issues in Maine, conspired to doom the Malaga community. Internationally, the

Malaga community shares a history not unlike those countless African communities in the Americas (known as maroon (Engl.), cimarron (Sp.) or quilombo (Bantu) who resisted bondage and struggled to maintain their freedom and independence. They too were destroyed physically, but their stories are beginning to be told. The Malaga story may in fact be directly connected to this global history of African diasporas for a ship named Malaga was built not far from the island in 1832 and was active in the illegal trans-Atlantic slave trade for many years (see McMahon essay).

At Malaga, that resistance came from the inner spiritual strength and endurance of the people themselves. Like those who survived the horrific “Middle Passage,” they may have come empty-handed, but not empty-headed. They may have been deprived of their material culture or physical homes, but not their spiritual essence – a concept that Daniel Minter envisions in his art that comes from his knowledge of Yoruba philosophy as lived by Yoruba descendants in Brazil where they are known as Nago. In Yoruba/Nago thought, one’s spiritual essence resides in the head, or more precisely the “inner spiritual head” (ori inu). It is this inner spirit that guides and shapes one’s path and possibilities in life. Holding true to one’s beliefs, one’s center, is crucial, for that spiritual essence is eternal, ever-present. At initiations, heads are painted with sacred chalk, marked with the signs and symbols of the deities that govern and guide one’s life and ori inu.

The Paintings

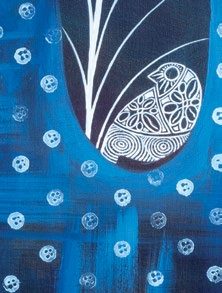

It is this invisible inner spiritual head that Daniel Minter makes visible in a number of his paintings. In Removal of Visible Presence for 100 Years – One, fish swim in the head of one Malaga ghost. She embodies the water goddess Yemoja, “Mother of Fish,” her head filled with sea life, her collar with unborn babies in wombs. Buttons cover her collar and dress, a reference to the labor of Malaga women as laundresses and seamstresses for the whites on the mainland. A tear-shaped bundle at her womb holds the gathered bones of ancestors. They are gone yet ever-present – a reference to those buried at the bottom of the Atlantic’s watery grave, as well as those bones that were disrespected, disinterred, and moved to a mass grave on the mainland where some Malaga residents were incarcerated.

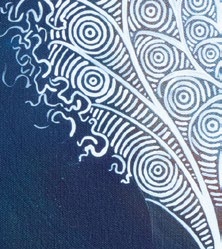

In Removal of Visible Presence for 100 Years – Two, a different but related spiritual head displays a spiral sea shell. The spiral is an African cosmic sign that heralds ever-changing life, afterlife, and possible return. And in a Yoruba/Nago context, a child born with “seashells on the head” (a full head of tightly curled or spiraling hair) is a child born through the intercession of Olokun, like Yemoja, an African deity of the sea. His spirit essence is linked with the sea. He is an omo Olokun, a “Child of the Sea God.” A bird within his garment may suggest a fluttering heart, a dream of freedom and flight, for he is dressed in a garment with a grid of vertical and horizontal stripes (or bars) that emerges from light below and rises to his shoulders cloaked in a sea of four-eyed buttons, also made from shells. Below, a bundle of bones evokes the departed.

These spirit figures are both real and unreal, they haunt us just like the histories they embody.

In Method One and Method Two Daniel Minter reminds us of our racist history. A caliper, an instrument used in the pseudo-science of eugenics to measure head/brain size and the supposed mental capacity of a person, floats in space. In the past, it determined a person’s life. It continues to haunt the present. Turn that instrument up-side down and the outline of a boat’s hull appears, evoking the nightmare of Middle Passages, those trans-Atlantic journeys into America’s “heart of darkness” and chattel slavery.

In Method One, Malaga Island (at dawn or sunset) tops the canvas. Just below, a boat floats submerged under the surface of the water, reminding us of that painful burden and memory of passage. As Daniel Minter once explained in an interview:

There is always this weight on us, and the boat is a weight you cannot escape. It’s colonization, and everything is viewed through that lens – the difficulty of escaping it and almost the impossibility of escaping it …. You can pretend it doesn’t exist. It doesn’t matter if you know it’s there. It doesn’t matter if you acknowledge it. The weight is always there. In some form, you’re always going to carry it.

(Minter interview with Bob Keyes)

Below the boat, a caliper hovers menacingly over a ghostly silhouette of a head. This ethereal head consists of translucent white patches and soft, delicate curly lines of hair (and mind, brain waves?) that float up and out. They contrast with the sharp, inward-curving metal caliper attempting to measure and stifle a person’s thoughts, dreams, and hopes.

In Method Two Minter powerfully summarizes the history of slavery and racism and its impact on the Malaga Island community. That burdensome boat-memory floats in dark waters at the top; in the middle, a menacing caliper used to control and destroy; and below, an uninhabited Malaga Island with only the memory of its human community.

Color

One of the first things one notices in this series of eleven canvases is the presence of certain colors – a sea of blues and blacks and delicate white lines. Various shades of blues and blacks permeate his figures and fill entire canvases, conjuring up the depths of the ocean, and a state of mind. There is a reason we say we have “the blues,” that feeling of sadness or longing, regret or nostalgia for something lost, perhaps tinged with anger. As music, the blues were created out of the hardships and struggles of African American life. It’s about being wounded or bruised, being “black and blue.”

For Daniel Minter, those indigo blues evoke multiple dimensions both historic and cultural. One is the horror of those tragic trans-Atlantic journeys that killed so many millions of souls, where only the strong survived and the bones of those who perished (or committed suicide) remain scattered on the ocean floor. Those same blue ocean waves lap the shores of Maine, the coast of Brazil, the beaches of Malaga Island, and the canvases of Daniel Minter. Yet, even as they evoke these heavy histories, those same blues honor the eternal spiritual presence and protection of Yemoja “Mother of Fish,” the Yoruba/Nago water goddess carried to Brazil and the Americas in the hearts and minds of enslaved Africans and celebrated today in countless places around the globe. Blues of many hues are her colors, for indigo is loved and praised. It is “cool and bright” as well as “deep and dark” like the unfathomable depths of the ocean. The myriad feelings and memories conjured by these blues are what give such power and resonance to Minter’s work.

The pervasiveness of blue is balanced with white – another sacred color of Yemoja. Her presence here may have been inspired by Daniel Minter’s time in Bahia-Brazil among the Afro-Brazilian descendants of Yoruba/Nago people (and others from Africa). White is coolness and composure, a sanctifying, cleansing color of rebirth and renewal of body, mind, and spirit. It is also the color of ancestral spirit presence. For all these reasons, Minter’s ethereal figures epitomize the persistence of the spiritual presence of those Malaga souls – scattered from their home, departed from this world, yet ever-present.

Red is another color that appears, but rarely – sometimes with striking force, at other times subtly. Dark red is the color of blood in our veins. It turns bright red in air. Red connotes heat and anger, action and energy. For Yoruba/ Nago, it is the color of one’s life force, “performative power” or àse. Note the striking red in the T-shirt worn in Witness to the Unseen – One, the collar of the man with a cap in Witness to the Unseen – Three and the subtle red in the eyes or throats of other figures. Perhaps red is the “fire” in Nyanen’s and Christina’s and Cheyanne’s songs?

Imagery

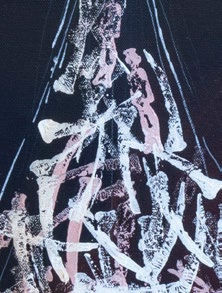

In this colorscape of blues, blue-blacks, white and flashes of reds, certain imagery appears repeatedly. The humans have an ethereal quality. They ar partial, translucent figures that seem to emerge from a watery world. The are like apparitions, phantoms of the past come to remind us of soul displaced that still wander among us. They are the “haints,” the haunting ones, ghosts. Their profiles recall the art of that ancient African civilization of Egypt, as well as the 20th century imagery of Aaron Douglass.

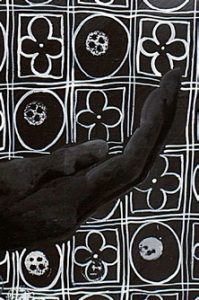

Many figures wear or hold buttons. For example, in Witness to the Unseen – One, a woman possesses a pendulous, tear- shaped bundle of buttons at her womb. Mostly made of bone or shells, buttons were found on Malaga in large numbers – evidence of the labor of girls and women who did the laundry and sewing for white families on the mainland. With layered meanings, these four- holed buttons recall the form of quatrafoils, a four-leafed plant motif that covers her garment. In an African diaspora religious context, such an image references a four-part kola nut, four cowrie shells, or the four-eyed sacred palm nuts (ikin), all of these used in Yoruba/Nago divination. Quatrafoils also visualize the leaves of a watery plant (ewere) that symbolizes Olokun, deity of the sea. And too, a variant of this circular motif may be inspired by the inside cross-section of okra, an African plant brought to Americas to make gumbo (its Bantu African name), and used as an offering in religious ceremonies. The figure’s muted blue presence contrasts with the bold red T-shirt and the hint of red in her staring eyes. Her blue and white headscarf is covered in birds in flight, as free as her flowing hair on the wind.

Buttons and plants fill Witness to the Unseen – Two (Cheyanne’s Fire). Cheyanne is a descendant of the Tripp family that lived on Malaga. Her “fire” is the burden she still carries, the powerful emotions she felt during her first visit to the island. The medallions on Cheyanne’s dress are circles filled with images for sustaining life: leaves, vines, plants, and okra interiors. A heavy bundle of buttons hangs below. Her large, heavily lidded eyes gaze off into the distance, remembering the past with sadness, and the future with concern. In Witness to the Unseen – Three, the profile of a man with billed cap, wears a large cape with quatrefoil leaves interspersed with a spider, turtle, lizard, rabbit, rooster, dog, bird, and fish – the flora and fauna on Malaga Island. Buttons cluster down the front, his shirt colored blue, black, and red. A subtle vertical red streak in his head turns to blue in his neck. A somber stare marks his facial expression.

Works entitled Nyanen’s Song – One, Nyanen’s Song – Two (Nyanen’s Fire), and the two versions of Christina’s Song — (Christina’s fire) refer to visitors to Malaga Island in the summer of 2018 who were deeply moved by the experience. They felt the invisible presence of those Malaga souls who made a life and built a humble community on the island. As Daniel Minter explained to me: “Christina is a descendant of one of Maine’s oldest African American families and Nyanen is a first-generation immigrant from Africa who came to Maine as a child.” He wanted to honor their presence and make the narrative in his work “more contemporary and less historical” – a history that lives in the present and must not be forgotten.

In Nyanen’s Song – One, she performs a gentle but firm gesture, cradling and protecting memories and dreams. Her gray and white garment is a grid of alternating squares of buttons and quatrafoils, each playing off the other. Her ephemeral presence emerges from the broad gray brush strokes of the background suggesting waving grass or water currents. Her blue face with eyes in an intense and solemn gaze conveys a strong resolve – she holds her center with strength and dignity despite the challenges. And in Nyanen’s Song – Two (Nyanen’s Fire), she hints at a gathering gesture with her right arm and hand and left reaching down toward a bundle of buttons. The okra motif fills her garment’s collar as her topknot coiffure rides high on her head, loose strands flying outward.

Daniel Minter has painted two versions of Christina, one in blue face with glasses, the second with reddish brown face. In one, fish, shells, birds, okra, and plants cover her garment. Her hand seems to shelter buttons below and her hair is a tangle of flying strands. In the second version – Christina’s Song – Two (Christina’s fire) – she is shown without glasses, her face in what appears to be a frown, her forehead wrinkled and her stare strong. Her transparency suggested in her brown emergence from a blue background make her an apparition.

The Installation

Daniel Minter has created a multi- sensorial experience to make real and tangible the presence, spiritual as well as lived, of the Malaga Island community. They are named and known individuals, the result of a long-term interdisciplinary project of archival, oral history, and archaeological work by many valued colleagues.

This presence is evident in everyday objects from Malaga – fish hooks, nails, iron stakes, fishing lines and weights, pottery shards, buttons, clay pipes and pipe stems, glass bottles, fish and animal bones – evidence of the hard-working lives of individuals. They help us imagine the touch of a sharp hook, the smell of pipe smoke, the taste of fish or chowder in a bowl, or the sound of a hammer striking iron. Displayed on rough wooden shelves or pedestals in and around an enclosure that evokes a Malaga home, along with photographs and captions, such objects not only attest to daily life, they embody those exiled souls. These objects, some made and handled over generations, possess accumulated, intensified spirit because of repeated human thought, touch, and action. They hold histories and lives. As Daniel Minter explained about tools he incorporated in an earlier exhibition called “Distant Holla,” “they held too much power… too much energy had been placed into them over the years…those tools were made for creating things, and should be honored.” Brought together by Minter, such objects make visible and tangible the invisible spiritual presence of those Malaga folks. That invisible human spirit, transferred to and embodied in the things they made, used, or consumed, makes this a restorative project. It recalls a shameful past and makes present those who were wrongfully exiled and shunned, reminding us they are still with us. Daniel Minter’s art reveals the spirit force of his ancestors and those of Malaga, the wise ones who managed to guard their spiritual inner heads and balance their anger and bitterness with the strength, determination, and will to survive and endure.

To learn more about OTHERED: Displaced from Malaga, download the informational PDF here.